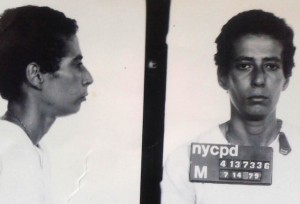

When Gloria Rubero was sentenced to 20 to life in 1981 for robbery and murder, the NYC subway fare was sixty cents; cigarettes cost 45 cents; and VCRs were a cutting edge technology. Twenty-six years later, Rubero, age 56, was released from prison into a city that she describes as “a time warp.” After spending the majority of her sentence at the maximum security facility at Bedford Hills,she had never used the internet, a cell phone or a MetroCard. On her first day out of prison, she saw people who seemed to be talking to themselves. Alarmed at the number of people she assumed were mentally ill, she asked her friend to bring her back to prison.

Across the country, the elderly prison population is skyrocketing. Between 1995 and 2010, the number of incarcerated people older than 55 has quadrupled. In New York State, as of January 2013, over 9,200 people (or nearly 25%) of its prison population are ages 50 or above.

In 2012, over 27,000 people were released from New York State prisons. Nearly half return to New York City. Almost 2,000 (or 13.2% of those released) were age 50 or older. Like Rubero, the majority had spent many years in prison, and they returned to a world that seemed like science fiction.

Lawrence White spent 32 years in prison, the majority at the maximum security facility at Green Haven, on a 25 to life sentence for his role in an armored truck robbery at the New Amsterdam Theater in 1975. He was in his seventies when he was paroled in 2007.

“People talk about the euphoria you feel about getting out,” he said. “I didn’t feel anything like that. I was scared to death and I certainly wasn’t happy. You don’t spend three decades in an eight-by-sixteen foot cell and then come out and expect to live a normal life. You become acclimated to prison life and get institutionalized.”

Although White now takes three trains to his office off Union Square each morning with ease, he recalls his first experiences on the subway. “By the next stop, I’d be soaking wet with sweat. I thought everyone was looking at me.”

While prisoners may hold jobs, they are often unable to find employment upon release. In prison, Rubero had worked as an electrician and plumber but was never issued a license. Out of prison, she was unable to find work in either field. Six months after she got out, Rubero finally found a part-time job in the maintenance department at the Osborne Association, a NYC-based group that helps people returning to society from prison.

According to Liz Gaynes, Osborne’s executive director, Rubero’s predicament is not unusual, particularly for people who have spent many years in prison.

“People may think they’re qualified to work, but often the skills they have aren’t currently in demand. They may have learned their skills on machinery that’s not up-to-date. They may not have recent references,” she explained.

The Osborne Association places people in job training programs. But, Gaynes noted, the jobs most available to people returning from prison are in foodservice and construction, both of which are more difficult for older people. “They may require lifting fifty pounds at a time,” Gaynes said. Desk jobs that do not require physical strength require technological savvy that those who are cut off from society for decades lack.

Mujahid Farid was sentenced to fifteen years to life in 1978 for attempted murder. He was released in 2011 at the age of 61 after serving 33 years, spending time in every male facility in New York State’s prison system. During his time behind bars, he had successfully litigated against prison conditions and sued over First Amendment issues after prison officials attempted to silence him. With those legal victories came monetary settlements, which Farid was able to stash away as a nest egg for his eventual release.

The money served him well. Before his arrest in 1978, Farid had worked as an offset printer. “During my time inside, I had considered not only working as a printer [upon my release], but possibly starting my own business,” he recalled. He soon discovered that the printing industry had all but disappeared and, with it, his hopes for employment.

Employment isn’t the only challenge. Finding housing, especially in an expensive city like New York, is also a problem. Upon release, Farid stayed with distant relatives in Queens, then in a transitional housing facility. “I found it difficult to find housing without credit,” he said. Fortunately, a man he’d known while in prison worked at a real estate office. He was able to help Farid find a one-bedroom apartment.

White was also fortunate. While running a program for lifers, he had developed relationships with groups that work with incarcerated people. One of these groups was the Fortune Society, a reentry organization. When he was released, he lived in the Castle, the organization’s 62-bed transitional housing complex in West Harlem. Later, he moved to a Section-8 building.

For Rubero, finding housing was not as easy. After finding a job, she searched for an apartment but was turned down repeatedly because of her criminal record. Finally, she said, a landlord told her that she could rent a unit in the South Bronx—if she paid one year’s rent up front. Between her and her wife Maria, who was also employed, they came up with the money and secured the apartment.

Many people released from prison are unable to come up with such exorbitant sums, if they can find employment and can afford rent at all. According to Gaynes, a majority end up in shelters or three-quarter housing, unlicensed, unregulated housing which often place up to six people in one room. Most nursing homes and assisted living centers do not want people with criminal records as residents.

Then there’s health care. Prison conditions—including inadequate medical care—often cause accelerated aging. Thus, a 50-year-old in prison often has a “physiological age” that is ten to fifteen years older. When released from prison, he or she is given thirty days of “walking meds.” Some may not have their medical records or know what medications they had been taking. After years of having prison staff dispense medications on a daily basis, some may be unaccustomed to keeping track of and taking medications on their own. Gaynes also estimates that 40% of aging people in prison have some form of cognitive impairment.

Aging people on parole from state prison are ineligible for Medicare coverage to help address their health care needs. If they meet income limits (which most do), they are eligible for Medicaid, but even obtaining that can be a challenge.

In the month between being approved for parole and being released, not a single prison staffer had told Rubero that she needed to start the process of obtaining photo identification. When she tried to apply for Medicaid after release, she was told she needed to have identification other than her prison ID.

So Rubero applied for her driver’s license. First, she had to figure out how to travel from the Bronx to the Department of Motor Vehicles, a trip she had not taken in over 26 years. She had to learn how to navigate not only a much-changed subway system, but also the crowds. When she arrived, she learned that she needed her birth certificate. That took a month. She also needed other forms of identification to meet the required number of points to obtain a license.

“We don’t know about these things inside,” she said. “Things change and they forget about us. We forget about these things too.” It was three months before she was able to receive Medicaid. In the meantime, her walking meds ran out. Fortunately, Rubero, who had suffered two strokes while in prison, experienced no adverse effects.

Even with health insurance, however, years in prison still take their toll. Rubero’s wife and co-defendant Maria Ramos was released shortly before she was. Five years later, Maria learned that she had stage four ovarian cancer. According to Rubero, Maria had never received gynecological exams during her 26 year incarceration. Maria had health insurance, enabling her to undergo both surgery and chemotherapy, but neither worked. She died at age 61.

“When you come out, you lack social capital. All your friends have died or moved away,” explained White, whose wife and mother had died while he was serving his prison sentence.

White’s case manager at the Fortune Society told him where to go to apply for identification, saving him the headaches that Rubero encountered. When he applied for his social security card, he learned that he was entitled to his deceased wife’s social security. He now lives off the monthly eight hundred dollars from her social security, supplemented by two hundred dollars in food stamps. The money allows him to devote his time to coordinating the Hope Lives for Lifers, an in-prison program for people with life sentences.

Farid has been home for three years. He found a temporary job monitoring the pre-arraignment pens through the Correctional Association of New York, a prison watchdog organization. “I made a lot of connections through that,” he said. From his experience appearing before the parole board ten times in eighteen years, he and other advocates, including formerly incarcerated people, began discussing ways to address the parole board’s reliance on a person’s original conviction as the benchmark for release. Out of these discussions came the Release Aging People in Prison(RAPP) campaign.

Under the slogan “If the risk is low, let them go,” RAPP mobilizes to change the routine in which parole and compassionate release are denied to those who have spent decades in New York’s state prisons. In 2013, Farid received a Soros Justice Fellowship to highlight ways in which prisons are ill-equipped to address the needs of aging and geriatric people and to increase opportunities for the release of aging people behind bars.

“When we launched the campaign, our main focus was to accelerate the release of elderly people in New York State prisons,” Farid explained. “We found no resistance in our communities. But what we did find were concerns about what happens to people once they are released. These concerns were a lot bigger than what we expected. So we shifted to address these concerns.”

That shift included reaching out to other organizations, both those concerned about people in prison such as the Osborne Association, which recently released “The High Costs of Low Risk” a white paper identifying issues facing the aging prison population, and those primarily concerned with the non-incarcerated aging population like the NYC Department for the Aging.

What came out of these initial meetings and discussions was the Aging Reentry Task Force. The Task Force includes the NYC Department for the Aging and officials from the New York State Department of Correctional and Community Supervision, as well as advocacy organizations like Osborne, the Correctional Association of New York, the Fordham School of Social Work, Columbia University’s Criminal Justice Initiative, and the RAPP campaign. The Task Force is creating a pilot project, which will involve geriatric assessments for prisoners over age fifty, special discharge planning for older people, including connecting them with available senior services, and training reentry providers in geriatric care.

Rubero has been home for seven years. This past March, she spoke at a symposium about reentry at Columbia University. It was her first time speaking in public.

“I was nervous. I felt awkward because everybody [else on the panel] had a position—lawyers, commissioners, parole,” she recalled. Since then, Rubero has become involved in RAPP and continues to speak out. “Anything that can help the women, I’ll do,” she said.

Victoria Law is a freelance writer and editor. She frequently writes about incarceration, gender and resistance and is the author of Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women.Her previous story for Gothamist concerned teenagers in solitary confinement on Rikers Island.Follow her on Twitter @LVikkiml