In the wake of the grand jury failure to indict for the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown, we are called to consider the highly questionable relationship between prosecutors and the police. But the oft-repeated, “a prosecutor can indict a ham sandwich,” mantra exists for a reason – that a prosecutor, should it be his or her sincere objective, can convince a grand jury to indict anyone or anything. Even a ham sandwich.

Perhaps the grand juries did not indict the police officers in both cases not because of the evidence or lack thereof, but because the prosecutor manipulated the grand jury to not indict. Given the generally codependent relationship between prosecutors and police, should the larger question and debate not be just over police violence, but prosecutorial misconduct? Willful manipulation and negligence by prosecutors?

I am a felon. Never had a single word carried so much meaning for me – the judgment of others, the passive presumption of a fair and objective justice system, guilt, shame, remorse, anger, and perhaps most importantly, release. The hope that I can fully unshackle myself from the notions that civil society would have me hobble in self-pity, encumbered by a scarlet ‘F’ for the rest of my life.

When the FBI first came knocking on my door, I picked the defense attorneys that most belittled my damaged ego and psyche. Perhaps I felt secure in their arrogance. I was scared. I didn’t think I was guilty of what I was being accused of, but I also feared a trial. Society does not look kindly upon white collar criminals, and I had seen a few cases where I felt guilty convictions had been won on a surge of populist anger towards Wall Street vs. the facts. I feared prison.

Little did I understand my lawyers had already made the decision for me. I was to plead guilty with the implicit promise that I would never see the inside of a prison. I protested, argued that I had lacked sufficient criminal intent to have known I was committing a white collar felony. But my protests were met with resolute conviction from my lawyers that my case would be a surefire loser at trial, and that I would undoubtedly, unquestionably face up to 15 years’ incarceration. They had already made the choice for me by presenting outlandish scenarios appealing to my worst fears.

And so my life irrevocably transformed overnight. The prosecutor was impressively clever, she had run circles around my counsel outthinking them at each step of the process. At distinct moments through my proffer sessions, I noticed smirks of self-satisfaction from her – the kind one feels when they’ve bluffed their way to a win in poker.

In the later years of my business career, I had become callous and negligent in my job – a reflection of my own growing cynicism in Wall Street and dissatisfaction with myself. Yet I somehow had faith that the ‘Justice System’ would be a different realm, one of fairness and truth, where prosecutors huddled in teams to debate the facts of potential prosecution giving in all cases, the benefit of the doubt. After all, prosecutors are being dealt the hefty responsibility of playing God with others’ lives.

I concluded this process allocuting a plea to a Federal Judge, professing guilt in cases where I knew I was innocent. I remain stupefied at how I arrived there. I equate it to slowly boiling a frog – that a frog would immediately jump out of boiling water but if the heat is increased ever so gradually the frog willfully neglects his own safety to his own demise.

I refuse to be bitter. And ironically, I am remorseful and I do accept responsibility. Not for the false pleas, but for my failed judgments leading up to and through the criminal justice process. I chose, of course, to always interpret right and wrong as close to the line as possible. To interpret right and wrong in the way that best suited my interests. In some cases, I know that I crossed the line. I chose to continue in an industry filled with narcissistic, quasi-psychopathic individuals, each year loathing myself a little more. And I chose to pick defense counsel that appealed to my most ignoble insecurities and instincts for self-preservation.

The isolation in the aftermath of a criminal conviction is indescribable. It’s unclear who amongst family and friends knows, and it is hard to know how to behave – withdrawn and remorseful, or to put on airs of normalcy. So many doors close – of course, the word ‘felony’ encompasses a wide range of delits – from stock option backdating & market manipulation on one end, to violent rape & pre-meditated murder on the other. For an educated person, the closed doors of employment & any career requiring a professional license, including driving a taxi, is a crushing implosion of conventional hope. I often went to bed praying for mercy from God that I would not awake the next day. The sun arose, it seemed, to mock me, to provide hopes and opportunities only to snatch it away. I prayed to melt away into the ether. Frankly, sometimes I still do.

We have focused much on the remorse, acceptance of responsibility and re-entry of felons into society. Let’s not forget the sins of the prosecutors. It is far more common that people are incarcerated for crimes they may have not actually committed as a result of plea bargaining because the unchecked power of the prosecutor allows no other option for the average individual. So often it is the ordinary career ambitions of an underpaid prosecutor that compels him to focus solely on the notches on his belt, to apply the same relative morality against the individuals he prosecutes.

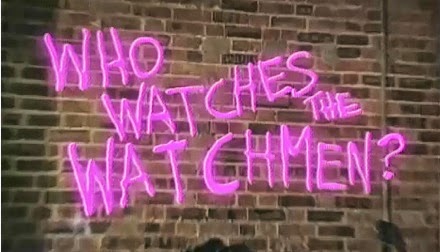

It is an abuse of power. The prosecutors are the watchmen in our society, but there is no agency watching over them. So whether it is the willful intent of a prosecutor to manipulate a ‘fail to indict’ in Ferguson or a prosecutor willfully holding exculpatory evidence from a defendant – let us question our blind faith in the integrity of prosecutors.

Because if we don’t watch the watchmen, no one else will.

– Anonymous, A White-Collar Felon