Editor’s Note: This is the second of a two-part series on prison profiteering schemes that provide inmate services at a high cost to a population that is disproportionately poor. Part one looks at money-transfer fees and the growing popularity of jail and prison-issued “release cards.”

The phone call Grace Bauer received from her son Corey, an inmate in Maryland’s Roxbury state prison, was one of desperation. An incident with other inmates the previous day made him fear that his life was in danger. “I had to call the prison and ask for help,” she recalled. Because her communication with Corey is limited to scheduled phone calls, Bauer could do nothing but wait anxiously to find out if her son was OK. “I went 24 hours without knowing if the prison took steps to keep him safe,” she said.

Even in the age of Facebook and Snapchat, most prisons and jails still rely on the telephone as the primary method of contact between inmates and their families. That’s begun to change, however, with a growing number of facilities adopting more immediate means of communication such as email from handheld devices, providing a way for inmates to stay in touch more regularly with family members. It’s a shift that Bauer, a longtime advocate for juvenile justice reform, welcomes. “If [Corey] had access to email I may have known right away that he had been moved to protective custody rather than having to go to bed worried to death,” she said.

For Chris Grewe, CEO of APDS (America Prison Data Systems), which provides prison-specific tablet computers to correctional facilities, email is just the tip of iceberg when it comes to bringing technology to those who are incarcerated. “We’re looking to provide education, rehabilitation and vocational training,” he said. “We’ve got Khan Academy [lectures] and other kinds of really robust educational materials. We replace recreational reading libraries, which are typically just a handful of donated books, with access to tens of thousands of titles in multiple languages.”

Proponents of email and mobile devices in correctional facilities believe this kind of technology has the potential, if deployed wisely, to drive down recidivism rates. A 2013 study by the RAND Corporation found that inmates who participated in educational programming were 43% less likely to return to prison than those who did not. A 2012 report by the Vera Institute of Justice reinforced previous research by detailing how regular contact with family members can reduce the risk of inmates becoming re-incarcerated once they’re released.

Bauer sees these and other benefits in her work as head of Justice for Families, an advocacy group for families with an incarcerated loved one. While it pains her that families have to pay for email services, she said “those that have access to it have been really happy with it.” Speaking of a mother who’s able to send pictures to her son, Bauer said the woman felt more strongly “like her son was still a part of the family.”

“We have this incredible opportunity,” said Brian Hill, co-founder of Jail Education Solutions, another provider of tablet-based educational software. Referring to the lack of meaningful resources currently available to inmates, he noted, “[They] are a captive audience with all the time in the world and right now we’re just showing them daytime television. Our focus is how do we take the technology that’s coming into this space and use it to make significant changes in people’s lives.”

“We have a disproportionately poor population in America’s jails. So now I’m going to tie their ability to learn and be educated to whether or not they have money to pay for it? That seems disingenuous.”

Robert L. Green

Montgomery Co. Dept. of Correction

Stronger family ties, educational opportunities and reductions in recidivism all go hand in hand with managing daily operations inside a county jail, said Robert L. Green, acting director of the Montgomery County Dept. of Correction and Rehabilitation. He’s begun a tablet program in his facility using hardware and software purchased from APDS. “If inmates are in their housing area doing something productive with their life,” he said, “something that interests them, there’s going to be less violence, I assure you.”

For those who see buying tablets for inmates as a luxury expense Green points to the educational resources they provide. “One teacher coming into a jail costs $50,000-$60,000 in salary and benefits,” he said. “If you can buy 15-20 tablets for $30,000 and circulate them among a large number of inmates, you tell me where the value is.”

As a 31-year corrections department veteran, Green is also quick to point out the cost of not educating inmates. “In local jails 94% of all of the people we touch are going back into our communities. How do you want them back? The value to society of extending the educational experience in every element that we can is huge,” he said.

Companies like those run by Grewe and Hill, with their exclusive focus on education and rehabilitation, are relying on economies of scale and the power of disruption to make a profit while bringing down the cost of technology and communication services. At scale, tablets can be provided at very low cost to facilities. Inmates pay no fees for the content. And there’s no technical barrier to someday replacing expensive telephone calls with much cheaper tablet-based broadband phone service.

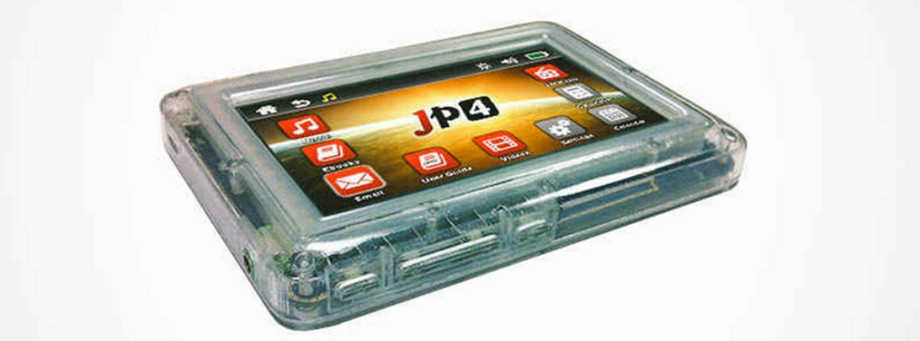

These goals run counter to the fee-based approach of the major players in the field such as JPay, Keefe Group, GTL and ATG. JPay has been a pioneer in the field, providing email service since 2006 and handheld devices since 2010 with more than 50,000 tablets in circulation across 11 states, according to a company spokesperson. This is in addition to its longer-standing and lucrative inmate money transfer business which in 2013 — fueled by high fees charged to family members — brought in $50 million in revenue, the Center for Public Integrity reported. The company recently announced it will become a subsidiary of Securus Technologies, one of the nation’s largest prison telephone vendors.

A review of vendor contracts and customer pricing across several states shows a continuation of this high-margin business model both by JPay and its competitors as they’ve expanded into software and hardware services.

Families of inmates in state and local facilities are being charged between $.25 and $.50 to send an email. Attaching a photo to the email typically doubles that cost. Inmates must also pay to send emails, with additional fees if they want a printout of an email or photo they’ve received. MP3 players and tablets are sold at prices ranging from $40 for a small capacity music player to $200 for a tablet that is several generations behind comparable consumer models. MP3 downloads are sold for almost $2 per song. “The prices are ridiculous compared to what you would pay on the street,” said Adryann Glenn, a former inmate who now mentors those returning home from prison.

A contributing factor to these high prices is that vendors pay a cut of the revenue generated by the email fees, handheld device sales and media downloads back to the state DOC or jail agency. These “commissions,” essentially legalized kickbacks, can be as high as $.05 per email and $12 per tablet. In other cases vendors simply pay a fixed percentage of the total fees they collect each quarter. These financial incentives have obvious appeal to corrections agencies faced with growing inmate populations and dwindling resources. “We deliver on our promise to increase your revenue by providing inmates’ families and friends with flexible payment options,” assures a pitch on one company’s site.

The problem, critics say, is that this revenue is being made off of those who can least afford it.

“I think we charge inmates enough already for stuff inside jails,” said Green. “We have a disproportionately poor population in America’s jails. So now I’m going to tie their ability to learn and be educated to whether or not they have money to pay for it? That seems disingenuous.”

“At the end of the day it’s not the inmate paying the cost, it’s the inmate’s family,” he added.

Grewe agrees. “It’s inherently unfair to charge an 83-year-old grandmother in Brooklyn to talk to her grandson,” he said. “We should be paying her … because the more often she stays in touch with him the less likely he is to screw up when we let him out.”