The evidence is piling up that too many Americans are wasting away in prison. The National Academy of Sciences, for example, recently concluded in a major two-year study that the United States “has gone past the point where the numbers of people in prison can be justified by the social benefits.” Other groups, like Human Rights Watch, the Brennan Center for Corrections, Corrections Today and the University of Chicago Crime Lab, have also raised their voices. Pope Francis, in his address to the International Criminal Law Association on May 30, called for major reforms of criminal justice systems.

The evidence is piling up that too many Americans are wasting away in prison. The National Academy of Sciences, for example, recently concluded in a major two-year study that the United States “has gone past the point where the numbers of people in prison can be justified by the social benefits.” Other groups, like Human Rights Watch, the Brennan Center for Corrections, Corrections Today and the University of Chicago Crime Lab, have also raised their voices. Pope Francis, in his address to the International Criminal Law Association on May 30, called for major reforms of criminal justice systems.

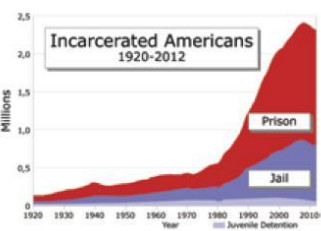

Here are some basic statistics. Having quadrupled in the past four decades, the prison population in the United States today is 2.2 million, or about one of every 100 adults. This rate far exceeds that of other Western democracies. Maintenance for each prisoner costs taxpayers $30,000 a year. Over half of inmates are locked up for nonviolent offenses. According to “Nation Behind Bars,” a recent report by Human Rights Watch, nearly one-third of those serving life sentences do not have the possibility of parole, and more than 40 percent of all federal criminal prosecutions are for immigration offenses. For every 100,000 Americans in each of the following groups, according to the report, there are 478 white males, 3,023 black males, 51 white females and 129 black females in prison.

Too often the system fails to treat prisoners as human beings; each person has a right to fair trial and punishment and equal protection under the law. President Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke for “the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.” The forgotten men and women of today are the 2.2 million in prison, committed by a public that too often bases its understanding of prison life on films and television and has been fed tabloid headlines about these “monsters” from the moment of their arrests through their trials. The surge in imprisonment began in the late 1960s with President Richard M. Nixon’s campaign for “law and order.” The accusation of being “soft on crime” replaced the “soft on

Communism” of the 1950s and has continued to influence American politics.

Many people have presumed that a correlation between crowded prisons and a reduced crime rate points to a significant cause-and-effect relationship, but recent research paints a more complex picture, according to a report this year from the National Research Council. The report concludes that the “magnitude of the reduction” of crime due to imprisonment is “highly uncertain” and “unlikely to have been large.”

The criminal justice system has changed significantly over the past 40 years. People are doing more time than ever before. Sentences have grown longer thanks to legislatures that want to appear tough on crime, most notably through mandatory minimum sentences and “three strikes” laws. States have also farmed out prison management to private contractors who run the institutions for profit. More convicts mean more money for their investors.

Families bear the consequences of incarceration. In the last two decades of the 20th century, the number of children with incarcerated fathers in the United States shot up from 350,000 to 2.1 million. In addition, former inmates have a hard time finding work or housing, and families can crumble as the behavior of children is influenced by the jail time of their parents. New laws must address the new reality.

Drawing from the Scriptures and the collective experience of the people of God, Pope Francis proposes that prisoners—through reparation, confession and contrition—should be able to return to society. Increased penalties, Francis said to the Criminal Law Association, do not solve social problems or reduce crime rates; in fact, they “may give rise to serious social problems.” Furthermore, he explained, “criminality is rooted in economic and social inequality” and in organized crime that exploits the most vulnerable. “A society that is governed solely by market laws and creates false expectations and superfluous necessities,” he said, “discards those who are not at the top and prevents the slow, the weak or the less gifted from taking an open road in life.”

The reformed prison of the future, aided by public and private high schools and universities, should educate inmates not just with job skills but with the liberal arts, instruments for moral rejuvenation. Sentences must be shorter. There should be alternatives to incarceration for those who suffer from addiction or mental illness. Elderly or ill prisoners who are not likely to re-offend can be released. Prisons must be evaluated on their success or failure in reducing recidivism. Judge Richard A. Posner writes in the New Republic (6/9): “The worse the treatment meted out to prisoners, the more recidivism there is, and thus the more crime.” Our country must transform the prison from a trash can where we dump offenders to an instrument for the public good.