At some point you gotta ask the hard questions… You gotta look beyond the obvious and ask the hard questions. I found this on Huffington Post Black Voices….

In Washington, D.C.’s public schools, African-American students are almost six times as likely to be suspended or expelled as their white classmates. Students with disabilities are also disciplined at higher rates than their peers.

But a group of local students is hoping to use their artwork to change that.

Students participating in a program with the nonprofit group Critical Exposurecontend that disciplinary practices in the District’s public schools contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline, which pushes minority and vulnerable students out of school and into the penal system.

For the past two years, Critical Exposure has brought students together to document the problems in their school district through more than just data and numbers. The students use photography and multimedia projects to depict the difficulty their peers face in finishing school as a result of tough disciplinary policies. Some of the student photographers have been suspended at some point during their educations, and many have seen friends and peers suspended for minor infractions.

“They see what happens when students get 10 days out of school with suspensions, how students get in trouble with the criminal justice system and juvenile justice system and how it snowballs from there,” said Adam Levner, the executive director and co-founder of Critical Exposure, in a phone interview with The Huffington Post.

Scroll down to see the students’ photos.

Levner said that members of his organization’s 2012-2013 after-school fellowship class identified the school-to-prison pipeline as a problem they wanted to document. The 2013-2014 fellows then chose to continue the project, while other program leaders brought the idea to individual schools as well. (The current class of fellows has not yet decided what it will be documenting.)

Since then, Critical Exposure students have testified at public hearings about the issue and had a series of meetings with D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Kaya Henderson. They also successfully worked this year to establish a pilot restorative justice program, which emphasizes discussion and conflict resolution over suspensions and expulsions, at a local high school.

Malik Thompson, 19, was involved with Critical Exposure throughout his high school career. He has experienced firsthand the impact of “school pushout.” Following his older brother’s death several years ago, when Thompson was in the ninth grade, he says he stopped going to his citywide, application-only high school. After several months of truancy, and what he describes as “minimal efforts” from school administrators to draw him back in, Thompson says he received a letter from the school informing him that he was no longer enrolled.

“Basically, I was kicked out,” Thompson told HuffPost.

The next year, Thompson became involved in Critical Exposure after seeing a flyer at his new school. He is now an intern at the Gandhi Institute in Rochester, New York, a nonprofit that helps promote racial justice and nonviolence education. There, he facilitates workshops for young people in schools while leading photography and videography efforts.

Thompson, who ended up finishing his high school career in a home-school program, also advocates for the expansion of restorative justice programs in schools.

Restorative justice, he said, “creates [a culture] where the entire student –- like what happened outside the school and during school — is acknowledged and taken into account.”

Thompson continued, “I think more programs like Critical Exposure should exist where young people have avenues to begin to experience their own power, to work collaboratively together with adult supporters in order to make change in their world.”

“Critical Exposure was essential to me becoming the person I am today,” he added.

Below are photos from Critical Exposure’s students, representing how they see the school-to-prison pipeline in their everyday lives, provided to HuffPost by Critical Exposure. All photo captions were written by individual photographers, but have been edited and condensed for clarity.

-

-

“Coming in the building feels like turning in my stuff before entering a jail cell.” — Angel L.

-

Untitled

“The teachers can go through the gate without being stopped, and students are stopped and asked to show a pass. Students are treated like they’re prisoners. They already have to be escorted by a teacher to get through.” – Karl L.

“The teachers can go through the gate without being stopped, and students are stopped and asked to show a pass. Students are treated like they’re prisoners. They already have to be escorted by a teacher to get through.” – Karl L. -

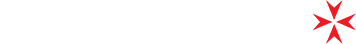

Ban The Scans

“This photo represents what we have to go through before entering our school everyday. I think it’s uncalled for, and nine times out of 10, if any violence … would occur it would be outside the school. According to DCLY [D.C. Lawyers For Youth] high quality mentoring for every D.C. child between 10-17 years old would cost $63 million, versus … paying $305 million just to incarcerate them.” – Sean “Lucky” W.

“This photo represents what we have to go through before entering our school everyday. I think it’s uncalled for, and nine times out of 10, if any violence … would occur it would be outside the school. According to DCLY [D.C. Lawyers For Youth] high quality mentoring for every D.C. child between 10-17 years old would cost $63 million, versus … paying $305 million just to incarcerate them.” – Sean “Lucky” W. -

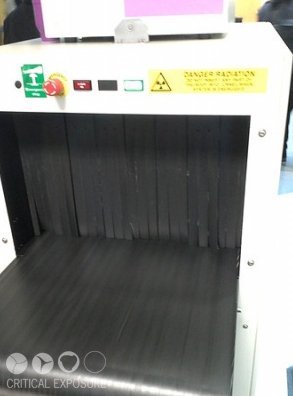

The Blind Pipeline That Youth Cannot See

“This photo represents how some African American youth are on a path to prison that they can’t see or don’t know when it’s coming. The reason I say that is because most of us are expected to go to prison sometime in life. Statistics say one out of three African American males will go to prison in their life. In elementary school us African American youth are predicted to go to prison or jail based on standardized test scores and suspension rates.” – Sean “Lucky” W.

“This photo represents how some African American youth are on a path to prison that they can’t see or don’t know when it’s coming. The reason I say that is because most of us are expected to go to prison sometime in life. Statistics say one out of three African American males will go to prison in their life. In elementary school us African American youth are predicted to go to prison or jail based on standardized test scores and suspension rates.” – Sean “Lucky” W. -

The Jail That Surrounds Us

“This is a picture of the black long gate that surrounds my school, with only three ways to enter and I know that this is a tactic that jails use to keep ‘criminals’ in or out.” – Mike

“This is a picture of the black long gate that surrounds my school, with only three ways to enter and I know that this is a tactic that jails use to keep ‘criminals’ in or out.” – Mike -

Rights

“The American flag symbolizes the rights we are granted as citizens and the freedom we have to manifest ideas and expand our knowledge. The bars represent restriction and confinement. Two conflicting ideas. We should not feel like our school system is detaining us and preventing us from flourishing.” – Anaise

“The American flag symbolizes the rights we are granted as citizens and the freedom we have to manifest ideas and expand our knowledge. The bars represent restriction and confinement. Two conflicting ideas. We should not feel like our school system is detaining us and preventing us from flourishing.” – Anaise -

Troubled Past

“My name is Jacqueline Smith I [have] live in Washington D.C. most of my life. Im 20 in the twelfth-grade and excited to graduate in 2013. It took until my last year to figure out how school and education was important. This year has really opened my eyes. Because back then even when I was little I didn’t understand why my mom woke me up early in the morning just to go to school because I never felt like it … In middle school I was suspended a number of times and got expelled from school. But when I was suspended I knew that I was free by staying home watching TV … I changed because I didn’t want to fail.”

“My name is Jacqueline Smith I [have] live in Washington D.C. most of my life. Im 20 in the twelfth-grade and excited to graduate in 2013. It took until my last year to figure out how school and education was important. This year has really opened my eyes. Because back then even when I was little I didn’t understand why my mom woke me up early in the morning just to go to school because I never felt like it … In middle school I was suspended a number of times and got expelled from school. But when I was suspended I knew that I was free by staying home watching TV … I changed because I didn’t want to fail.” -

The Everyday Routine

“Everyday students have to enter through the auditorium doors and place their backpacks on the X-Ray machine. Then they walk through the metal detector to meet their bag on the other side and then must wait for the bags to be searched by a security guard. This makes students feel as if we’re going inside a jail to meet someone, or as if the staff sees us as criminals. Statistics show that 70 percent of students [who are] involved in ‘in-school’ arrests or are referred to law enforcement are black or Latino. If DCPS [D.C. Public Schools] wants to lower these numbers then why do we have the same procedures of entering a jail [instead of] a comforting environment of being welcomed to school?” – Mike

“Everyday students have to enter through the auditorium doors and place their backpacks on the X-Ray machine. Then they walk through the metal detector to meet their bag on the other side and then must wait for the bags to be searched by a security guard. This makes students feel as if we’re going inside a jail to meet someone, or as if the staff sees us as criminals. Statistics show that 70 percent of students [who are] involved in ‘in-school’ arrests or are referred to law enforcement are black or Latino. If DCPS [D.C. Public Schools] wants to lower these numbers then why do we have the same procedures of entering a jail [instead of] a comforting environment of being welcomed to school?” – Mike -

Untitled

“This photo is of a young man who is sitting at a desk. The desk is in the school hallway and he is the only one outside. ‘My teacher put me out here.’ In most cases, the student is not at fault. Sometimes teachers do not know how to deal and give appropriate punishments. Restorative Justice should be implemented in our schools because, not only does it help students learn how to deal with their behavioral problems, it trains our teachers to deal with students in a correct manner that doesn’t allow their personal judgement to affect the student.” – Samera

“This photo is of a young man who is sitting at a desk. The desk is in the school hallway and he is the only one outside. ‘My teacher put me out here.’ In most cases, the student is not at fault. Sometimes teachers do not know how to deal and give appropriate punishments. Restorative Justice should be implemented in our schools because, not only does it help students learn how to deal with their behavioral problems, it trains our teachers to deal with students in a correct manner that doesn’t allow their personal judgement to affect the student.” – Samera -

The Box

“Every morning for the past three months after walking through the metal detectors, 17-year-old Skinny has to explain to the security guards before being wanded why the machine went off. Skinny has an ankle monitor on, or ‘the box.’ With a curfew of 8 p.m. every night, he feels trapped and isolated from the world. Skinny is on probation and was told he would get the monitor off a month ago. When that did not occur he became disappointed. At times he refused to go to school due to his frustrations. D.C. public schools allow up to three unexcused absences until truancy reports are sent out. I am very concerned about his education and the consequences from the days he has missed.” – Samera

“Every morning for the past three months after walking through the metal detectors, 17-year-old Skinny has to explain to the security guards before being wanded why the machine went off. Skinny has an ankle monitor on, or ‘the box.’ With a curfew of 8 p.m. every night, he feels trapped and isolated from the world. Skinny is on probation and was told he would get the monitor off a month ago. When that did not occur he became disappointed. At times he refused to go to school due to his frustrations. D.C. public schools allow up to three unexcused absences until truancy reports are sent out. I am very concerned about his education and the consequences from the days he has missed.” – Samera

-